Ranking Soy Traders' Performance on Deforestation

Assessing the sustainability efforts of six of the largest soy traders

Introduction

Soy production in Brazil continues to be a major driver of deforestation and land conversion. In 2018 alone, over 2.9 million hectares of deforestation were cleared – an area the size of Albania - of which over 60 percent was due to commodity production[1]. Within the soy industry, only a handful of traders dominate the industry with six companies accounting for over half of all soy exports[2]. Moreover, none of the largest traders have successfully implemented zero deforestation or zero conversion supply chains, continuing to contribute to the mounting land conversion in Brazil.

This report examines the sustainability policies and performance of six of the largest soy traders to determine which traders have the most – and least – land impacts and land rights violations in their supply chain. The analysis is intended to illustrate to buyers, including consumer goods manufacturers and retailers, how certain traders offer less risk, and less environmental and social impacts compared to their peers. Compared to the worst performing traders, their better performing peers are viable alternatives to which buyers can transfer their contracts in order to avoid being complicit in widespread ecological destruction.

One dimension that these scores do not cover is the very real and damaging impacts these soy traders have on local and Indigenous communities. Soy expansion in Latin America often entails land grabbing, violations of Indigenous rights, and violence against local peoples.

Campesinos living among soy and cattle operations in Bolivia. Photo: Jim Wickens/ Ecostorm

Campesinos living among soy and cattle operations in Bolivia. Photo: Jim Wickens/ Ecostorm

While no systematic data exists to quantify the human and land rights abuses of these six soy traders, investigations have uncovered egregious abuses. Mighty Earth’s investigative teams have visited Indigenous communities whose traditional territories have been cut down and transformed into soy fields whose crops are exported overseas. They have heard a village leader describe the fear his community feels when planes fly overhead and spray pesticides for soy just a few hundred meters away, and the grief they experienced when several children died after drinking water from a discarded pesticide container found in a nearby soy field. Soy producers, ranchers, and illegal logging interests have too often used violence to displace Indigenous communities.

For more on these issues and investigations, please see:

- Cargill: The Worst Company in the World

- The Ultimate Mystery Meat: Exposing the Exposing the Secrets Behind Burger King and Global Meat Production

Methodology

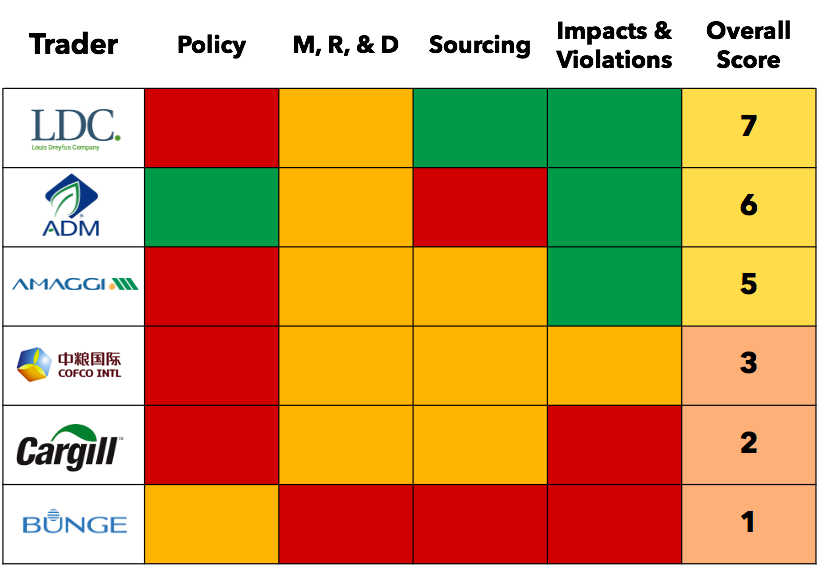

We assessed the six traders – Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Amaggi, Bunge, Cargill, COFCO International (COFCO), and Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) – in four areas of sustainability including 1) sustainability policy; 2) monitoring, reporting and disclosure; 3) sourcing areas, and; 4) observed impacts and violations.

The observed impacts and violations are based in part on Rapid Response reports in which a trader has known supply chain links. This includes group-level and property-level linkages. The full methodology details all types of supply chain linkages included in the analysis.

Findings

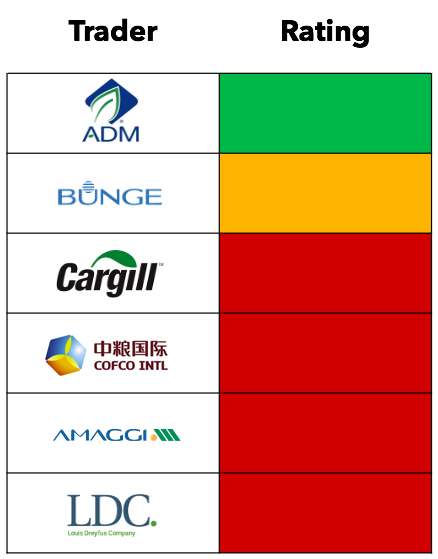

In combining trader scores across all categories, Bunge and Cargill score the worst, followed closely by COFCO. In contrast, Louis Dreyfus, Amaggi, and ADM score notably better, however no trader achieves a score worthy of praise. Regardless of issues within all traders’ supply chains, it is clear that Bunge and Cargill stand apart from the rest in terms of their weak soy sustainability policies, insufficient monitoring, reporting, and disclosure, high risk sourcing areas, and most importantly, the large volumes of clearance within their supply chains.

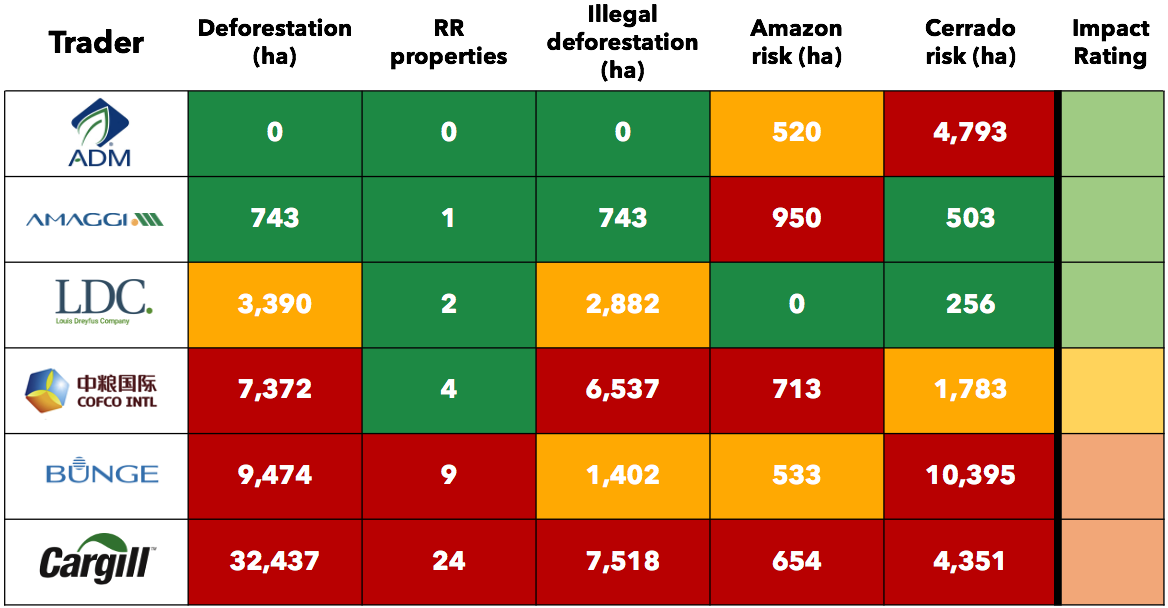

Impacts and Violations

The impacts and violations of the traders is weighted heavily as it represents measured amounts of deforestation within their supply chain. While the other categories in the analysis capture intentions and implementation practices, this category most fully captures the sheer scale of impact the traders have on native ecosystems through civil society monitoring efforts.

Impacts and Violations

Impacts and Violations

Bunge and Cargill score significantly worse than their peers, with Cargill scoring lowest in all indicators in this category. Cargill was associated with more than three times as much deforestation as Bunge or COFCO in the first half of 2020, as measured by Rapid Response reports, with over 32,000 hectares of clearance detected in selected farms supplying them. In comparison, Louis Dreyfus had approximately 10% as much clearance at 3,390 hectares, with Amaggi even lower at 743 hectares, and ADM at 0. More than a quarter of all the clearance in Cargill’s supply chain is potentially illegal, as is also true for Bunge. While COFCO had less total clearance, approximately 88 percent of that clearance was potentially illegal.

Data from Trase provides a complementary perspective with data for all of Brazil on deforestation risk – deforestation associated with soy expansion proportional to the volumes of soy sourced by each trader. In 2018, Bunge had over 10,000 hectares of deforestation risk in the Cerrado – more than five times the acreage of Louis Dreyfus, the best performing trader on this indicator. Cargill and ADM also notably had 4,351 and 4,793 hectares of deforestation risk in the Cerrado for this year.

Overall for impacts and violations, Bunge and Cargill scored worse than their peers due the greater amounts of clearance spread across more properties, and their higher deforestation risk in both the Amazon and Cerrado.

Category Scores

Policy

While all six traders have a deforestation policy specifically pertaining to soy, they vary in their strength. ADM is the strongest due to having a commitment to traceability, a near-term target date, and inclusion of small farmers. However all of the soy traders lack two crucial policy elements – a commitment to a clear cut-off date for deforestation and conversion, and a commitment to gender equality. In terms of addressing unsustainable land use, a clear cut-off date is essential to indicate a commitment to excluding soy from deforested and converted land from their supply chain. Cut-off dates in other commodity sectors, such as palm oil and cattle, have been successful in order to establish a benchmark upon which companies can be held to account.

Monitoring, Reporting, and Disclosure

All six traders score poorly in this category, with Bunge scoring slightly worse for failing to have an established grievance procedure. Most notably all soy traders fail to utilize a credible monitoring system to ensure soy in their supply chain is deforestation and conversion free. While the traders report progress annually, this reporting is insufficient since they are not effectively reporting on the outcomes of monitoring efforts, and instead reporting on incremental measures towards monitoring such as percent of their supply that is traceable. Without a credible monitoring system, the traders have no means by which to detect deforestation and conversion in their supply chain, and therefore cannot provide any assurances to buyers regarding the sustainability of their soy.

Sourcing

The category of sourcing reflects the geographic investment of each trader, with some traders having de facto lower risk supply chains based on having developed assets in areas that did not become frontiers of deforestation. The risk of sourcing does not necessarily reflect good practices of the company, but does importantly signify the likelihood of deforestation and conversion in their supply chain based on the origin of the soy. ADM, Cargill, and Bunge score poorly due the high proportion of their soy that originates in the Cerrado – 44 percent, 39 percent, 37 percent respectively – but ADM and Bunge stand apart for their failure to fully trace direct suppliers in priority municipalities. While Cargill, Louis Dreyfus, and COFCO have achieved 100% traceability in these municipalities, ADM and Bunge are at, or below 95 percent traceable, despite years of efforts dedicated to this end. Full traceability of direct suppliers – and indirect suppliers – is essential to enable sufficient monitoring within their supply chains.

Policy

Policy

Monitoring, Reporting, and Disclosure

Monitoring, Reporting, and Disclosure

Sourcing

Sourcing

Conclusion

The very low scores of Bunge and Cargill in this analysis suggests that their customers must demand immediate and robust improvements to their sustainability practices, and until those are implemented the traders should be suspended from buyer supply chains. While the other traders fail to provide deforestation and conversion free soy supplies, buyers can minimize their risk and reduce the overall impacts in their supply chain by transferring contracts to these higher scoring traders.

The contractual action from buyers sends an important market signal: remove deforestation and conversion from your supply chain, or the market will look elsewhere.