By buying wood pellets from the US southeast, Japan is fueling forest degradation, hazardous pollution

“So, kind of a funny story,” said Tom Brennan, standing forlornly in a clearcut near his home by North Carolina’s Albemarle Sound. It had been, up until very recently, 87 acres of hardwood forest.

“When they first pulled the chipper up, I wanted to kind of remain anonymous. These were woods right here. And I was hiding in these woods, taking videos. And then, all of a sudden, I came one day and my little hiding spot was just completely gone.”

Brennan sought to understand what would happen to this land. “The forester told me this would not be replanted.”

“You don’t think it will naturally recover?” asked Sayoko Iinuma, part of a delegation from Japan to whom Brennan was showing the clearcut.

It will eventually, Brennan clarified, but may not be the same type of forest. And, at any rate, “We don’t have 50 to 75 years for carbon sequestration,” he said, referring to trees’ ability to absorb and store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, a vital function as the climate crisis worsens. Estimates indicate that the 87-acre hardwood forest here had been sequestering roughly 14 million pounds of CO2, capturing more and more each year as the trees grew. The carbon sequestered in these trees will be released back into the atmosphere when they are burned.

The group was visiting this clear-cut in rural North Carolina because, as Brennan’s investigation had confirmed, at least some of the logged trees had been sold to Enviva Inc. Enviva is the world’s largest wood pellet producer, staking its rapid expansion on exports to Japan. Wood pellets are a type of biomass fuel that can be burned to generate electricity. While often classified as renewable, wood releases large quantities of heat-trapping carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere when burned—exacerbating climate change.

Iinuma and the rest of the delegation from Japan came to investigate what Japan’s rapidly increasing demand for wood pellets means for southern forests, local communities, and the global climate. They visited forests in current and potential sourcing areas for pellet mills in Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, and Mississippi.

Sayoko Iinuma, staff of the Japanese nonprofit Global Environmental Forum

Sayoko Iinuma, staff of the Japanese nonprofit Global Environmental Forum

Tom Brennan, a North Carolina resident concerned by the wood pellet industry

Tom Brennan, a North Carolina resident concerned by the wood pellet industry

Tom Brennan speaks about clear cut with Japan delegation

Tom Brennan speaks about clear cut with Japan delegation

Biomass in Japan

Following the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster, the Japanese government introduced incentives to hasten the adoption of renewable energy. The government considers biomass to be renewable and supports the industry with a subsidy known as a feed-in-tariff (FIT) that pays a generous fixed price for renewable electricity as it is generated over time.

The incentive worked as designed, allowing biomass power plants to expand and increasing biomass usage dramatically. Demand for wood pellets soon outstripped domestic supply. Japan’s imports soared from just 72,000 metric tons in 2012 to 1.6 million metric tons in 2019 and 4.4 million metric tons in 2021. By 2019, only 8.4% of wood pellets consumed in Japan were produced domestically.

As of September 2021, 1,998 MW of biomass capacity approved under FIT’s “general wood” category—using mostly imported wood pellets—has started operation, with even more planned. Additionally, coal plants are beginning to burn woody biomass alongside coal in order to evade climate change regulations and operate for more years.

The 2020s are the crucial decade for reducing emissions, and all metrics indicate that we are decidedly not on track. Over 500 scientists and 170 environmental groups have warned that emissions from burning biomass will add more CO2 to the atmosphere in the critical coming decades, setting us back in the fight against climate change.

“Biomass burning is doubly dangerous, as it both increases emissions and takes away the most effective means we have to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere—living forests,” explained Roger Smith of Mighty Earth.

The forest biomass pellet production industry has also been shown to contribute to forest degradation in the US southeast. Furthermore, civil society groups, impacted communities, and the media have raised environmental justice concerns about pollution from wood pellet mills, which are predominantly located in low-income communities of color.

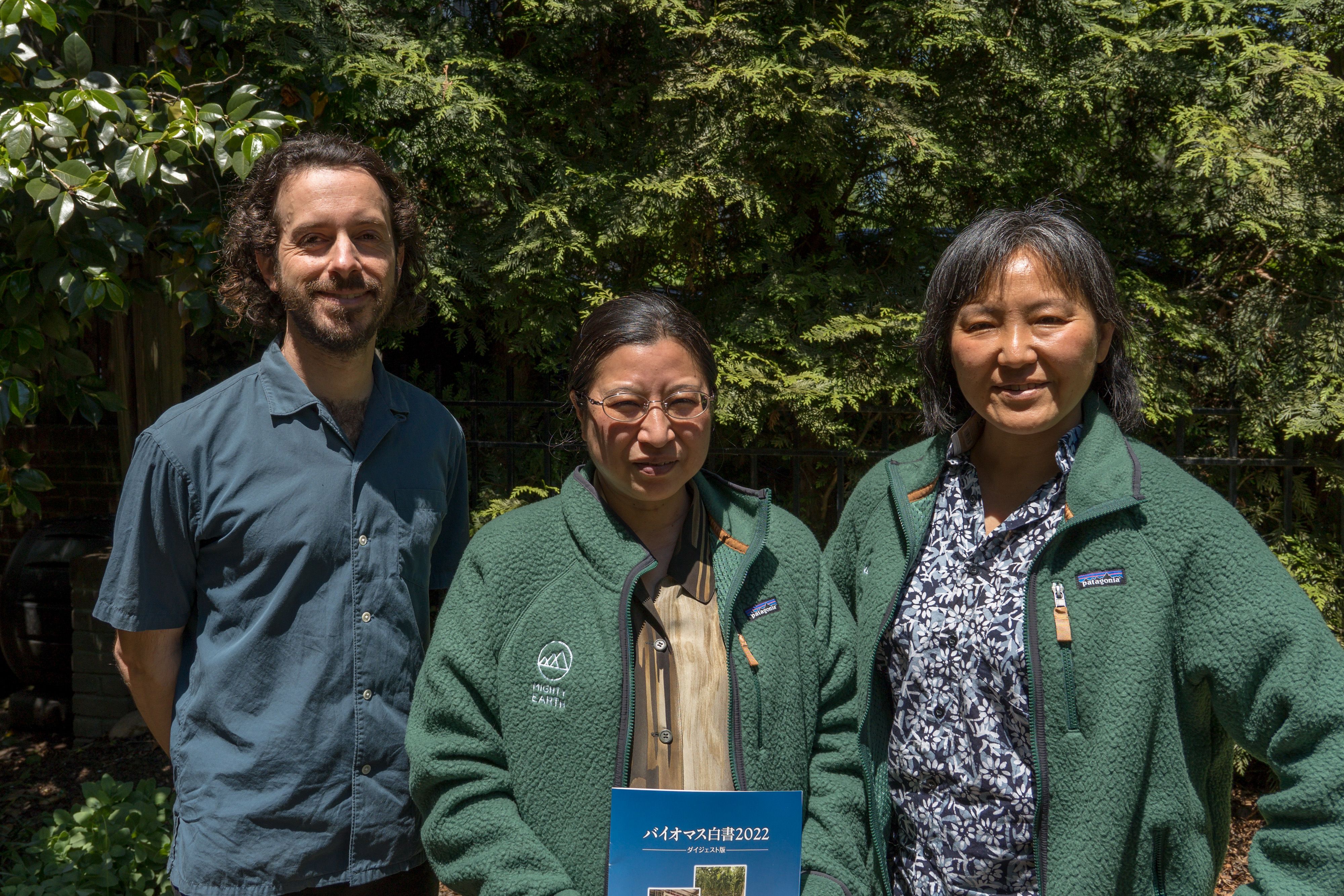

(left to right) Mighty Earth's Roger Smith, Biomass Industrial Society Network's Miyuki Tomari, and Global Environmental Forum's Sayoko Iinuma

(left to right) Mighty Earth's Roger Smith, Biomass Industrial Society Network's Miyuki Tomari, and Global Environmental Forum's Sayoko Iinuma

These were all reasons prompting the Japanese delegation’s May 2022 tour of wood pellet mills, their sourcing areas, and nearby communities in the US southeast, as, going forward, the region is set to produce vast amounts of wood pellets for export to Japan. The delegation was comprised of Sayoko Iinuma, a forestry specialist at the Global Environmental Forum; Miyuki Tomari, a leading expert on biomass and chairperson of the Biomass Industrial Society Network; and Roger Smith, Japan director for Mighty Earth.

Feeding the Biomass Beast

Japanese corporations have signed supply contracts with the world’s largest wood pellet manufacturer, Enviva, which operates 10 pellet mills in the US southeast. The contracts currently total an annual 3.5 million metric tons of pellets. In addition, Japanese utility J-POWER has signed a memorandum of understanding with Enviva to explore the potential to supply an additional 5 million metric tons.

“To produce 8.5 million tons of wood pellets, more than 200,000 acres of southeastern forests would need to be cut down each year. This is equivalent to a forest area four times larger than Washington, DC,” Tomari said in a presentation to US Congressional staffers at the end of the delegation’s tour. “If nothing is done, trillions of yen [tens of billions of dollars] will be spent on projects that run counter to climate change mitigation measures, and North American forests will be cut down. We want to avoid that.”

An Enviva investor presentation stated that Japanese customers will make up roughly half of the company’s contract mix by 2025, a doubling from 2019. Enviva plans to nearly double production capacity again from today’s 6.2 million metric tons to approximately 13 million metric tons by 2027, with plans for an additional 6 large new pellet mills to meet this soaring demand.

Enviva’s largest Japanese customer is Sumitomo Corporation, which has contracted Enviva to provide over 1 million metric tons of pellets annually, representing roughly 15% of its production in 2025. In addition to trading pellets to other companies, Sumitomo operates biomass power plants and has begun building a 112 MW woody biomass power plant in Sendai, Japan. Mighty Earth reports, released in 2019 and 2021, exposed the corporation’s pattern of investment in dirty energy, including biomass.

“If nothing is done, trillions of yen [tens of billions of dollars] will be spent on projects that run counter to climate change mitigation measures.”

“Trees that would normally never be cut for years and years”

Driving through Virginia and North Carolina from pellet plant to pellet plant, the group passed countless barren tracts of land. Tangles of branches strewn across the bald dirt hinted at the forests that had stood there until very recently. Iinuma and Tomari silently recorded mile after mile of video of this scarred landscape. Some cuts had a facade-like row of trees along the road, but gaps between the trunks betrayed the barren landscape spreading out for acres behind. They were surprised that clearcutting, the most ecologically damaging form of forestry, was the norm here.

Enviva purchases wood from independent contractors to make pellets, making it difficult to trace wood from specific logging sites to the company. Trees from a given cut will usually be sold for multiple uses, depending on their size, quality and other characteristics. As the delegation drove through the southeast, they passed many clearcuts and log hauling trucks on the road, but none bore any mark directly linking them to Enviva.

Enviva publishes general data about sourcing locations, though only covering July to December 2021. The company discloses that most of their pellet feedstock comes from forests, with sawdust and mill residues comprising only 20%. In the past, regional environmental nonprofits such as Dogwood Alliance have repeatedly followed logging trucks from clearcut sites to Enviva pellet mills. In October 2022, an activist investment firm uncovered hidden GPS data for sourcing embedded in Enviva’s website, and correlated this data with satellite images with hundreds of clearcuts.

Tom Brennan, who lives near the clearcut he showed the Japanese delegation, says the trees were ground into wood chips on site. He observed the truck as it traveled to Enviva’s pellet mill in Ahoskie, North Carolina.

One key concern with the wood pellet industry is that it has opened a new market for so-called “low value” wood that otherwise might not be cut. According to the North Carolina Forest Service, “bioenergy/fuelwood” production, which includes wood pellets, already comprises 12% of trees logged in the state and continues to grow.

“I think the logging companies know that they can take down very small trees now that normally would never be cut for years and years,” Brennan said. Unlike forest products that require sizeable, straight timber like boards or poles, pellet producers can utilize smaller trees.

“If a logging company were to come in here ... they would have selectively gone in and taken out those big trees. Good loggers don't clear-cut for big wood,” Brennan added.

Later, he showed the Japanese delegation a stand of hardwood trees planted roughly 25 years ago to illustrate how long it takes a natural stand of hardwoods to grow back. Most of the trees were still small enough for a person to fit their hands around the trunk. Pointing to nearby trees that were closer to 100 years in age, Brennan said, “These guys are the real lungs.”

Degraded Gulf Forests

In the bright Florida sunshine, the Japanese delegation watched as truck after truck carrying tree trunks and wood chips arrived at Enviva’s pellet mill in Cottondale, Florida. This massive pellet plant produces approximately 780,000 tons of pellets annually and was the first Enviva mill to produce pellets for Japan.

“A truck carrying whole logs came about every three minutes, and trucks with wood chips about every ten,” Iinuma said. “We saw just how incredibly fast these pellet mills consume wood.”

A truck carrying timber arrives at Enviva's pellet plant in Cottondale, Florida

A truck carrying timber arrives at Enviva's pellet plant in Cottondale, Florida

Despite the damage that the wood pellet industry has done to North Carolina forests over the last decade, Iinuma noted that the forests of the Gulf region appeared to be in even worse shape, with a much higher concentration of plantations. Especially near the Gulf Coast, the landscape was dominated by mile after mile of evenly spaced rows of spindly pines. In some places there were char marks from controlled burning that had been employed to remove understory and give priority to the faster-growing pines. In less-managed forests, palmettos and a mixture of hardwood saplings peeking out between the thin pine trunks hinted at what natural forests would look like if left alone to grow.

Underbrush regrowing in a pine stand in Mississippi

Underbrush regrowing in a pine stand in Mississippi

Brad Alexander, a trained forester who lives next to a proposed Enviva pellet mill site in Stone County, Mississippi, explained that the poor soil quality near the coast made it less ideal for growing trees. He hypothesized that Enviva’s proposed mill in Stone County and its recently completed mill in nearby Lucedale, Mississippi, both with capacities of more than 1 million tons of pellets per year, will be bringing the bulk of their raw materials from further inland, north of the mills.

A road leading into a clearcut in Mississippi

A road leading into a clearcut in Mississippi

Trees in the Gulf are rarely given the chance to grow long enough to become thriving forests. Alexander described one primary forest he had seen before it was cut: “It was like going back in time. I mean, humongous pine trees, dogwood trees under them … It was pretty awesome to go see it. But it’s gone.”

“We saw just how incredibly fast these pellet mills consume wood.”

Governments in Japan and Europe incentivize the biomass industry, which in turn pays landowners to cut trees at younger and younger ages, but is there a better way to use public funds? One that could deliver win-wins for communities, the climate and ecosystems?

Scientist William Moomaw and others have concluded that “proforestation” is best strategy to utilize forests to fight climate change. Rather than plant new trees, proforestation focuses on increasing the ability of existing forests to store carbon. This can be achieved by protecting natural forests by lengthening cutting cycles and reducing logging, stopping the conversion of natural forests to short-rotation plantations, and restoring degraded forests, such as those in the southeast.

Polluted Communities

Wood pellet manufacturing facilities produce air pollution at every stage of operation. The two major types of greatest concern for human health are emissions of particulate matter and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Health impacts of particulate matter, especially of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), are well understood. Fine particulate matter can travel deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. Numerous scientific studies have linked inhalation of fine particulate matter to chronic and acute health impacts including asthma, difficulty breathing, heart attacks, and premature death. A single large-scale wood pellet mill with pollution controls can still emit more than 100 tons of PM 2.5 per year.

The second major type of pollutants of concern, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), are present in green wood itself and are released into the air during drying and processing of the wood. The EPA classifies certain VOCs found in wood, such as formaldehyde, as carcinogenic. VOCs can also act as precursors to other pollution, combining with sunlight to form ground-level smog. Smog can cause inflammation and damage to the lungs and is suspected of causing asthma and aggravating other lung diseases. In addition to these two major forms of pollutants, wood pellet production also emits carbon monoxide.

A resolution approved by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Board of Directors in October 2021 states that “the hazardous and toxic manufacturing of wood pellets has proven to be a clear-cut case of environmental injustice by wood biomass industries, mostly locating their operations in close proximities of low-income communities and/or communities of color.”

Pellet plants abiding by the Federal Clean Air Act are permitted to emit 250 tons of regulated pollutants annually, an amount that, although legal, can still be very damaging to the health of people living near the plant. Making matters worse is the fact that investigations have uncovered that many pellet plants emit air pollution well in excess this legal limit, with patterns of violations continuing for years.

“The hazardous and toxic manufacturing of wood pellets has proven to be a clear-cut case of environmental injustice”

On their southeast tour, the Japanese delegation spoke with residents who have been impacted by wood pellet mills. Their first meeting was in Northampton County, North Carolina, where an Enviva mill is located. Sitting in a circle in a single-room community space, residents Belinda Joyner and Richie Harding spoke about how fugitive dust from the mill stains houses and cars, how 18-wheeler trucks drive noisily throughout the day and night, and how residents’ taxes went up 6% to provide a tax break for Enviva.

“There’s dust, noise, and we have animals who are out of their habitat [due to deforestation],” Harding said. The pellet mill “creates a lot of issues for people that have health concerns. I have lupus, I have a lung issue, and it’s not good for me.”

Harding and Joyner took the delegation from Japan to a neighborhood abutting the pellet mill. “Even in just the time we were standing there talking, we could feel small dust particles from the mill in our eyes and nose,” Iinuma remembered.

The Japan group speaks with residents living near the Enviva pellet plant in Northampton County, North Carolina

The Japan group speaks with residents living near the Enviva pellet plant in Northampton County, North Carolina

In Portsmouth, Virginia, where Enviva operates a port facility to ship wood pellets to customers in Europe, scientist Gary Harrison expressed to the group his concern about emissions from diesel trucks carrying wood pellets. According to Harrison, the trucks pass through low-income communities near the port every 15 to 20 minutes, 24 hours a day.

“Because of the diesel, they are releasing PM 2.5 diesel particulate, nitrous oxide, and other toxins every single day,” Harrison said. As demand for pellets grows, “that means more trucks, and more trucks means more air pollution.”

Scientist and environmental justice advocate Gary Harrison in front of an Enviva wood pellet shipment facility (background) in Portsmouth, Virginia

Scientist and environmental justice advocate Gary Harrison in front of an Enviva wood pellet shipment facility (background) in Portsmouth, Virginia

The most serious community impacts the Japanese delegation saw were in Gloster, Mississippi. In this small town of less than 1,000, residents live near a pellet mill operated by British utility and pellet producer Drax, and they suspect it to be damaging their health.

“I worry about actually dying, about not breathing,” said Gloster resident Shelia Dobbins, who lives half a mile from the mill. Dobbins experienced trouble breathing after the Drax mill opened, and she now requires oxygen 24/7. Others present at the meeting spoke about similar difficulty breathing, increased rates of bronchitis, nosebleeds, and other health issues.

“So many people are sick behind this plant,” Dobbins said, at times becoming emotional. “They’re worried about money. I’m worried about my health.”

In November 2020, the Drax Amite mill in Gloster was fined $2.5 million by the state for emitting three times its permitted level of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The Drax mill in Gloster isn’t an outlier: A 2018 report by the Environmental Integrity Project found that 11 out of 21 pellet mills surveyed “either failed to keep emissions below legal limits or failed to install required pollution controls.” In 2022, Drax agreed to pay $3.2 million in fines for pollution violations and install pollution controls at two pellet mills in neighboring Louisiana. Mississippi notified Drax of violations of hazardous air pollution limits in 2023.

Gloster residents Shelia Dobbins (left) and Carmella Wren-Causey spoke with the Japan delegation in Gloster, Mississippi

Gloster residents Shelia Dobbins (left) and Carmella Wren-Causey spoke with the Japan delegation in Gloster, Mississippi

Carmella Wren-Causey, the Gloster resident who organized the meeting with affected community members, and who also suffers from difficulty breathing, was indignant about the way her community had been treated.

“What is it doing to our children, our senior citizens? What is it doing to our community, period? Why is no one talking about it? Why weren’t we notified [about the pollution]?” As she spoke, her voice was frequently drowned out by the roar of trucks carrying tree trunks on the nearby road.

Carmella Wren-Causey warning communities about the dangers of wood pellet plants

Carmella Wren-Causey warning communities about the dangers of wood pellet plants

Later, the delegation visited a cluster of trailer homes separated from the Drax pellet mill by only a chain-link fence. “Although this mill has a lower production capacity than Enviva facilities, we could see huge stacks of whole trees,” observed Iinuma. “There were also piles of chips and residuals out in the open, so it wasn’t hard to imagine that when the wind blows, dust and other particles will be blown into the surrounding area.”

Residents living near the Drax pellet plant in Gloster, Mississippi, are experiencing health issues they believe to be caused by the plant

Residents living near the Drax pellet plant in Gloster, Mississippi, are experiencing health issues they believe to be caused by the plant

In Enviva’s case, analysis by CNN found that eight out of the company’s then nine operating pellet mills were in communities with a higher percentage of Black residents than the states as a whole; similarly, eight out of the nine communities also had higher poverty rates than the state average. More broadly, a resolution approved by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Board of Directors in October 2021 states that “the hazardous and toxic manufacturing of wood pellets has proven to be a clear-cut case of environmental injustice by wood biomass industries, mostly locating their operations in close proximities of low income and/or communities of color.”

More communities are at risk of pollution from the rapid growth of this industry. At present, 28 pellet mills are in operation in the southeastern United States. Ten more have been planned or proposed, with the expansion largely focused on exports to Asia.

“So many people are sick behind this plant. They’re worried about money. I’m worried about my health.”

Demand Japan Fix its Energy Policy

It’s time for Japan to change its energy policies that are worsening climate change, hurting vulnerable Americans, and accelerating the loss of natural forests in North America.

There is hope found in a recent precedent where the Japanese government and companies fixed their mistakes:

Japan has also subsidized the burning of palm oil to make electricity. However, after criticism from scientists and environmental experts that palm oil production is a major driver of the loss of tropical forests in southeast Asia, Japan retroactively required sustainability certifications and imposed a lifecycle greenhouse gas emission standard. Several Japanese companies felt such intense opposition within Japan and globally that they abandoned plans to build palm oil-burning power plants.

No energy source should be subsidized as renewable if it harms forests, and worsens climate change.

Now it’s time to address the problems with wood biomass being subsidized under the feed-in-tariff scheme and being burned in coal power plants. No energy source should be subsidized as renewable if it harms forests, worsens climate change, and burdens communities with air pollution.

The Japanese government, as well as Japanese companies such as Sumitomo Corporation that import or use wood biomass, need to set and apply strict greenhouse gas limits to all biomass electricity production. This needs to take into account carbon dioxide emissions associated with production, transportation, and the burning of the wood. Simply reporting emissions is not enough; they need to be reduced and then eliminated in the coming decades to stop global warming.

Furthermore, these institutions need to implement stringent sustainability requirements to protect forest health—including prohibiting biomass sourced from natural forests and biomass that is made from whole trees (rather than the scraps and sawdust the industry claims it uses).

Thirdly, is that while the Japanese government requires imported biomass to be produced in accordance with local laws, there must be checks and enforcement to make this meaningful. In this absence, Japanese importers should do their own due diligence and suspend imports from pellet mills found to violate federal or state laws, including the Clean Air Act. Legality is of course a minimum, and responsible companies should adopt best practices following the recent settlement in Adel, Georgia whereby the pellet mill operator agreed to continuous pollution monitoring, transparent sharing of pollution data with the community, and that they must stay within pollution limits to be able to operate.

No energy source should be subsidized as renewable if it harms forests, worsens climate change, and hurts communities.

These are constructive next steps the Japanese government and businesses should take.

Japan policymakers should:

1. End subsidies for biomass power generation

2. Set and apply greenhouse gas limits to all biomass power generation

3. Implement sustainability requirements to protect forests for biomass imports

4. Enforce legality requirements and block imports from pellet mills found in violation of federal or state laws

The US southeast shows what impacts the biomass industry can have on vulnerable forests and communities in absence of sufficient regulation. Community members’ health and quality of life is being negatively impacted by Japan’s use of forest biomass. With ten additional pellet mills contemplated for the southeast US, they are counting on Japan to rethink its reliance on imported wood biomass and shift to renewable energy solutions that are truly sustainable for both environmental and human health.

Video message to Japan from the community in Stone County, Mississippi

Video message to Japan from the community in Stone County, Mississippi

As Ruth Storey of Mississippi implored in a video message to Japanese decision makers: “Please find another way. Don’t exploit the poorest people in America.”