Burning Paradise: Palm Oil in the Land of the Tree Kangaroo

What happened when a giant Korean conglomerate set its eyes on Indonesia's largest intact rainforest--and how that palm oil made it into the world's soap, moisturizer, and gas tanks

In the pristine rainforests of Papua, tree kangaroos hop among the trees, and birds of paradise dance in unmatched displays of brightness and beauty. Here, the magic of nature has flourished for millions of years, far from the reach of global agribusiness. But there is an acrid smell hanging in the air.

When you try to find the source, you come to a road that is blocked by heavy machinery and piles of recently cut timber – the remnants of the tree kangaroos’ homes. A large board reads “Palm Oil Concession of Korindo”.

Just above the tree line, on what just months earlier was a rainforest alive with the sounds of birds of paradise and the bouncing of tree roos, there is only orange mud and haze-filled air. The trees were all systematically burned to make way for a massive palm oil plantation owned by the Korean-Indonesian company Korindo.

Korindo knows that burning these native forests is illegal under Indonesian law, so they do everything they can to keep journalists out. They block the roads, lie to the press, and blame the Papuan people, the majority of whom never consented to the brutal destruction of their land in the first place.

For years, Korindo’s palm oil has ended up in the mouths and on the bodies of consumers in Europe, North America, China, India, Japan, and Korindo’s home country of Korea through a variety of products like doughnuts, toothpaste, moisturizer, soap, shampoo, candy, cookies, lipstick, and so much more.

Korindo’s palm oil has also ended up in the gas tanks of drivers who unwittingly purchase palm oil-based biofuel as part of European and Indonesian biofuel mandates and subsidies. Most of these consumers and drivers are unaware that their gas tanks may contain palm oil from a company responsible for destroying the habitat of the tree kangaroo.

But there is some hope that change may be on the way. In response to these findings, two of Korindo's direct buyers--the palm oil traders Wilmar and Musim Mas-- stopped sourcing from Korindo because it was violating their No Deforestation, No Peat, and No Exploitation (NDPE) policies.

Following these suspensions, on August 9, 2016, a Korindo subsidiary called PT Tunas Sawa Erma, which has 25,000 hectares of forest remaining in its three concessions, announced a moratorium on new forest clearing over the next three months as it develops a NDPE policy. However, Korindo fell far short of action to end deforestation and land rights abuses across its sprawling palm oil and timber operations.

Mighty, a new environmental organization launched by the Center for International Policy, in collaboration with Waxman Strategies, partnered with the research organization Aidenvironment to analyze Korindo's practices using satellite images and hotspot data. In addition, the Mighty team ventured into Korindo’s remote palm oil plantations in Papua to document the company’s actions. The photos and video in this report are from this investigation. (To see the full library of high resolution photos and videos, click here). This investigation was done in partnership with the Korean Federation for Environmental Movements (KFEM, Korea’s largest environmental NGO), the Indonesian organizations SKP-KAMe Merauke and PUSAKA, Rainforest Foundation Norway, and Transport & Environment. The full report of their findings is available here.

While this report focuses on Korindo's palm oil operations, its timber and paper operations are also damaging to the Indonesian rainforest.

The Last Frontier

The Island of Papua

Papua is the farthest eastern province of Indonesia, and home to some of the last untouched rainforests on the planet. It is one of the most remote, hardest to get to parts of Earth. Over the last 50 years, agribusiness has pushed into almost every corner of Asia, but until recently, Papua was mostly untouched – and is still largely intact.

Papua, Indonesia.

Papua, Indonesia.

Filled with orchids and ferns, and away from large-scale human disturbance, these lush rainforests host a full 50 percent of the entire Indonesian archipelago’s biodiversity. Although Papua is governed as part of Indonesia, it is part of the same continent – Oceania - as Australia. Like everything else east of the Wallace Line – the deep ocean trench that divides the two continents - Papua’s flora, fauna, and people are much closely related to those of Australia than anything in the rest of Indonesia. Once you reach Papua, you’ve left the realm of tigers, orangutans, rhinoceroses, and elephants, and entered the kingdom of the marsupials - a magical, strange and largely undisturbed galaxy of bowerbirds, cassowaries, cuscus, and tree kangaroos.

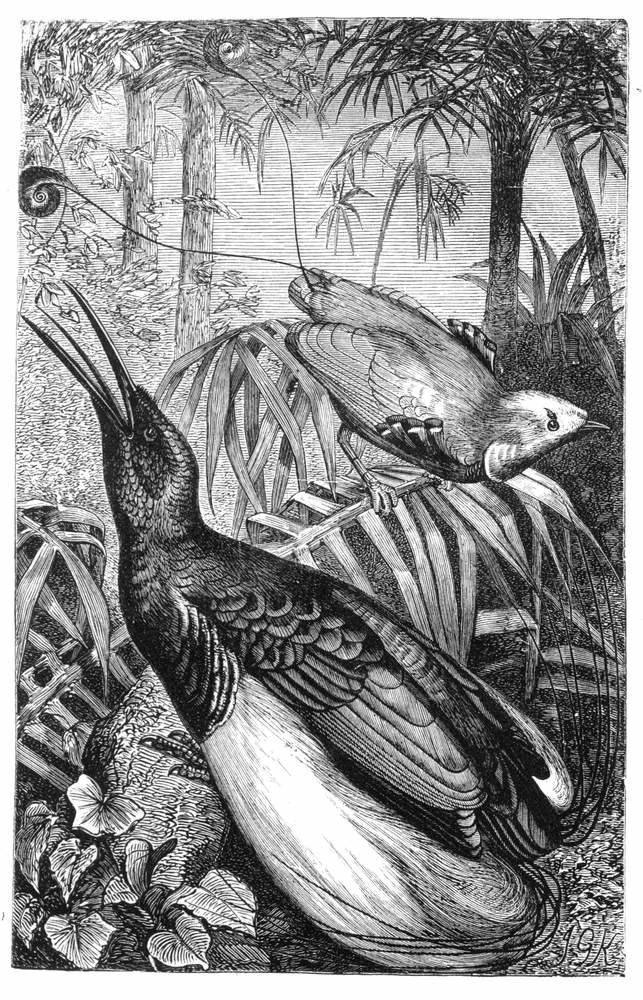

Wallace's drawing of a bird of paradise, from his 1869 book "The Malay Archipelago"

Wallace's drawing of a bird of paradise, from his 1869 book "The Malay Archipelago"

In fact, the area where Korindo currently operates in North Maluku was one of the stops of British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace on his famous eight-year Indonesian expedition. On the expedition, Wallace was astounded by the area’s biodiversity, and it enabled him to gather the 100,000 insect, bird, and animal specimens that helped him develop the theory of evolution along with his contemporary Charles Darwin.

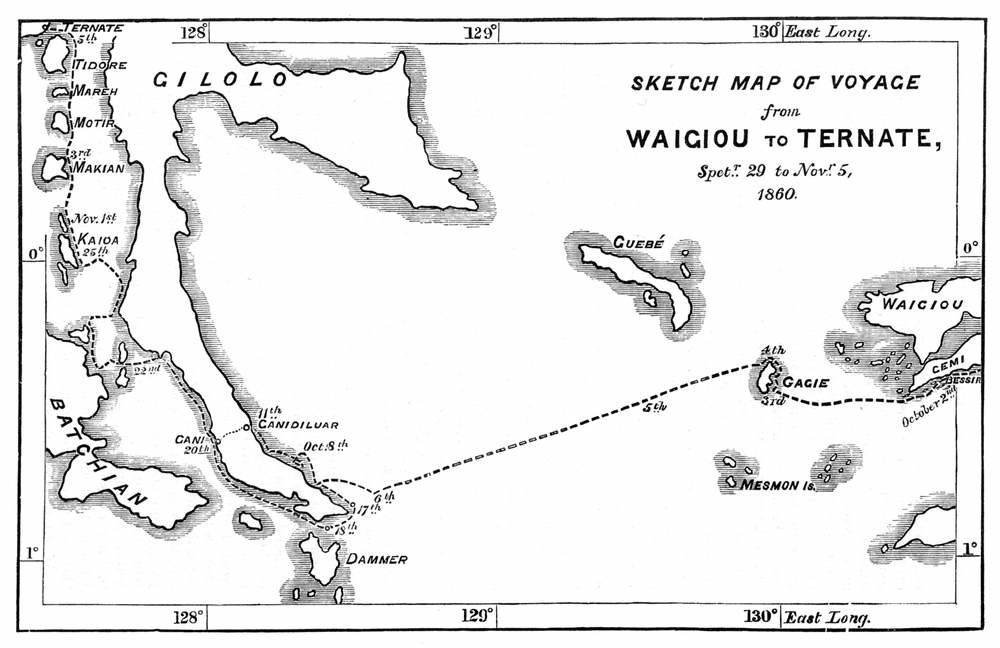

A map of the Wallace line, a faunal boundary that separates the ecozones of Asia and Wallacea, which is a transitional zone between Asia and Australia.

A map of the Wallace line, a faunal boundary that separates the ecozones of Asia and Wallacea, which is a transitional zone between Asia and Australia.

But Korindo’s systematic bulldozing and burning of this paradise has helped push the tree kangaroo and its cousin, the cuscus, to the brink of extinction. Unlike the common kangaroo, tree kangaroos have adapted to life in the trees – they have shorter legs, stronger forelimbs, and a long tail that they can used for balance or to hang from branches like a lemur. There are 14 species of tree kangaroo, all of them native to tropical rainforests in Papua, Papua New Guinea, and parts of Australia. Most species have seen their numbers sharply decline and are now at great risk of extinction due to hunting and a loss of habitat. The golden-mantled tree kangaroo, discovered in Papua, has been victim of habitat destruction and hunting, and has lost 99% of its historical range.

Tree Kangaroo in the Papuan rainforest. Credit: Bustar Maitar/Mighty

Tree Kangaroo in the Papuan rainforest. Credit: Bustar Maitar/Mighty

The cuscus, an animal endemic to the region.Credit: Greenpeace

The cuscus, an animal endemic to the region.Credit: Greenpeace

Bird of Paradise. Photo: © Greenpeace / Takeshi Mizukoshi

Bird of Paradise. Photo: © Greenpeace / Takeshi Mizukoshi

Local indigenous communities have also suffered from Korindo’s operations. One of Korindo’s concessions is in North Maluku, where most of the communities, who have lived there for hundreds of years, are strongly opposed to an oil palm plantation. Korindo is disregarding their customary rights by continuing its operations there. In a span of just a few years, Korindo has destroyed the forests that many Papuan communities have called home for centuries.

A family from the Kowin Marind tribe whose land is affected by deforestation caused by Korindo's plantation company PT Papua Agro Lestari. Credit: Mighty

A family from the Kowin Marind tribe whose land is affected by deforestation caused by Korindo's plantation company PT Papua Agro Lestari. Credit: Mighty

There are 3.6 million people in the region of Papua, including 312 different tribes and several uncontacted peoples. Korindo, a foreign company with no historical connection to Papua, presents a great threat to the Papuan people’s way of life. It is nearly certain that Korindo’s plantations will be short-lived: the company is likely to take its money and run. But, unless it invests in massive restoration, it will leave behind a devastated landscape that can no longer support the great diversity of food and people it once did.

On Korindo’s website, the company claims to be fulfilling their “responsibilities toward protecting Indonesia’s environment and furthering the advancement of its people”.

Yet Korindo has refused to identify or conserve critical endangered species habitat or forests within their concessions, a practice that is increasingly the norm among other oil palm companies.

The Deforestation of Paradise

Korindo

Korindo, a company whose name constitutes a composite of the words Korea and Indonesia, is the largest palm oil company in Papua. The company’s main businesses are in natural resources, with operations involving logging, pulpwood and oil palm concessions, and plywood, wood chip and palm oil production. Other Korindo businesses include newsprint paper manufacturing, heavy industries including wind towers, financing, and real estate. Korindo is controlled by the South Korean Seung family. The South Korean Hyosung Corporation owns 15% of two of Korindo’s plantations where the company is actively clearing forest.

Deforestation

Founded in 1969, the Korean-Indonesian conglomerate entered Papua to begin logging operations in 1993 and developed its first oil palm plantation in 1998. Korindo has eight concession areas in Papua and North Maluku totaling 160,000 hectares. In total, it has cleared more than 50,000 hectares of forests in Papua since 1998, an area approximately the size of Seoul, South Korea. Since 2013, the company has aggressively accelerated its clearing and burning of the land to plant palm oil plantations, destroying 30,000 hectares of forests from early 2013 to May 2016. 11,700 hectares of these were primary forests. On its website, Korindo states a target of 200,000 hectares of oil palm plantations by 2020.

Korindo plywood promotional video

Korindo plywood promotional video

Korindo recruits heavily from South Korean forestry schools to staff its operations in Indonesia. These young students, passionate about the environment, often join Korindo thinking they are going to plant trees. What they don’t realize is they will have to chop down and burn the rainforest before planting oil palm seeds.

The land clearing process that Korindo uses starts with a process called lining, which involves carving out the plantation blocks in the forest. Next, the team logs the high-quality timber to sell. After this, they clear the forest using bulldozers or excavators. They then push wood residue and branches into stacked rows to prepare it for burning. The team then sets the wood rows on fire. Since there is a high volume of biomass in the Papuan forests, the fires will quickly accelerate the breakdown process. If a burn does not fully incinerate the remnants of the forest, Korindo may put the wood rows on fire for a second time a few weeks later. The final step in the process is planting the oil palm plants.

Korindo's Operations in Tree Kangaroo Habitat

Fires

In May 2016, a Korindo representative responded to an inquiry by the major Korean news magazine SisaIN, saying, “Our company does not create plantations through intentional man-made arson.”

However, satellite evidence uncovered by Aidenvironment points to the contrary, revealing Korindo's systematic use of fire during the land clearing process. Satellite images show that the hotspot locations closely mirrored Korindo's land development. This means the fires could not have been natural or set by local communities, as Korindo argues, given that the affected areas shift year by year and directly follow Korindo's activities. Below is just a small sampling of evidence of Korindo’s deforestation and burning for palm oil (for more information, see the full report).

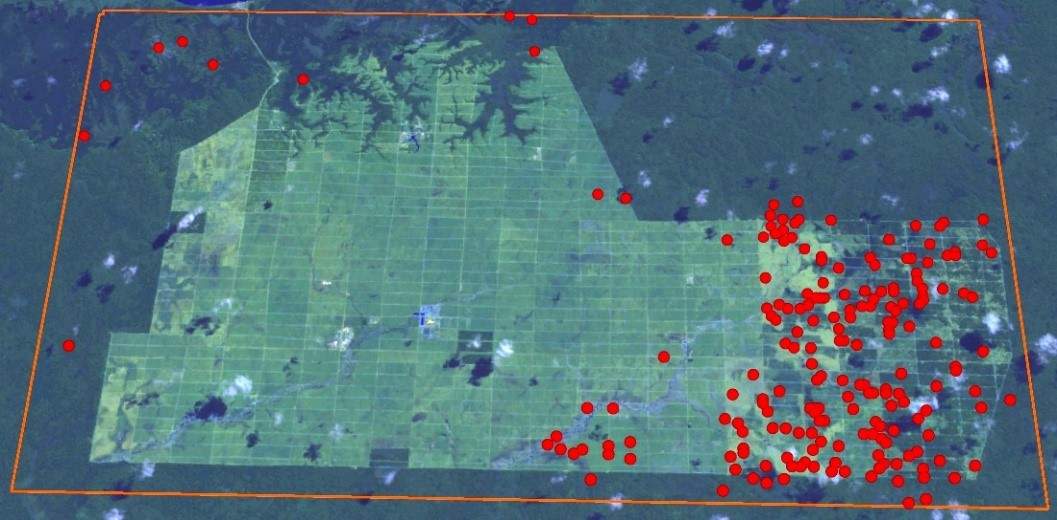

PT Donghin Prabhawa Concessions

In total, 351 hotspots were recorded in PT DP, spread throughout the period 2013-2015 (43 in 2013, 144 in 2014 and 164 in 2015). The fires typically followed a few months after deforestation, making it clear that Korindo used the fires to clear the biomass from the land to get it ready for planting. Note that there were almost no fires in the forested area surrounding the plantation development, and also no fires in the areas that were already planted with oil palm. This shows that fires occurred during the land clearing process.

The images below show the recorded hotspots in 2013, 2014 and 2015, each overlaid with a satellite image of their respective years.

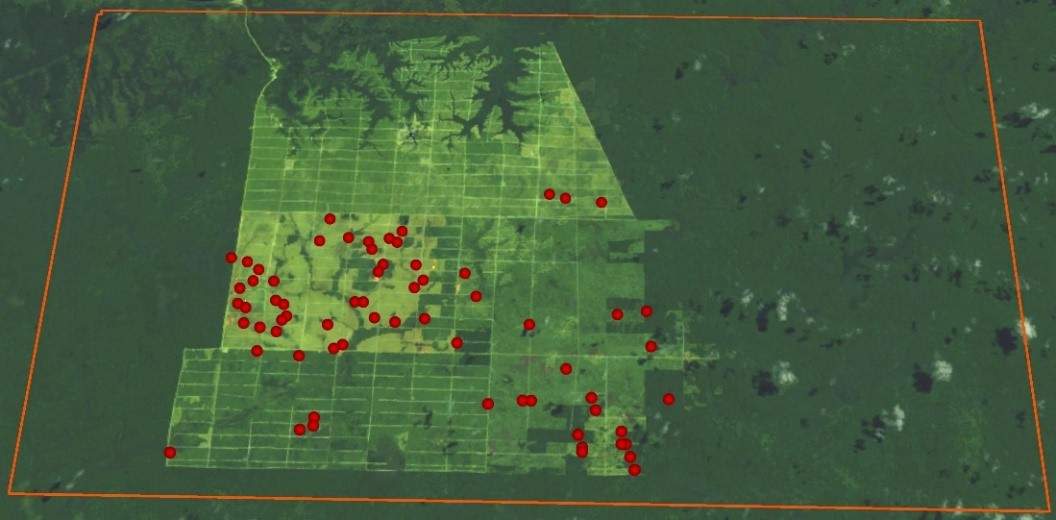

August 19-21, 2013 There were 43 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2013. Landsat 8 imagery.

August 19-21, 2013 There were 43 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2013. Landsat 8 imagery.

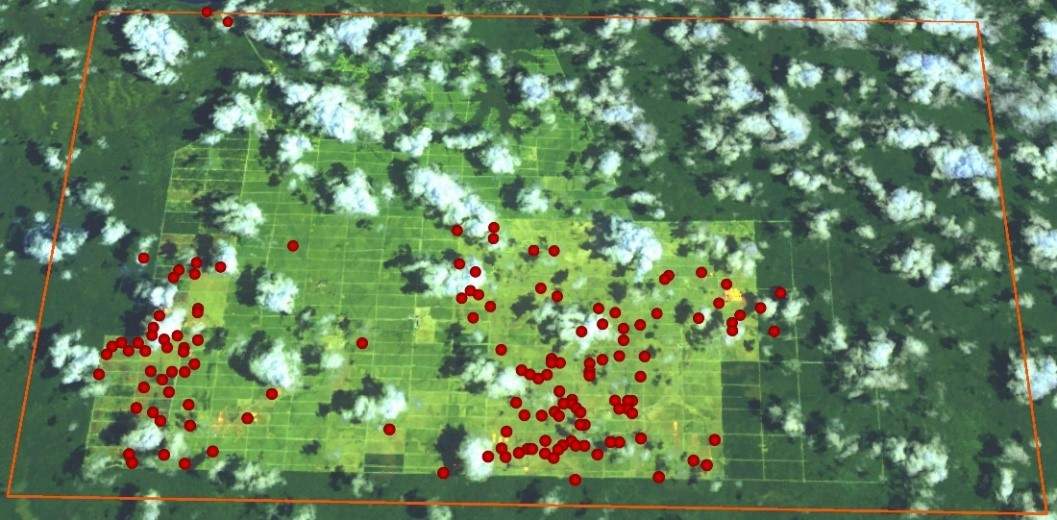

October 24 - November 1, 2014There were 144 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2014. Landsat 8 imagery.

October 24 - November 1, 2014There were 144 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2014. Landsat 8 imagery.

June 16-26, 2015 There were 164 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2015. Landsat 8 imagery. Sources: FIRMS, Fire Information for Resource Management System, http://go.nasa.gov/27awNFg.

June 16-26, 2015 There were 164 hotspots recorded in Korindo's PT DP in 2015. Landsat 8 imagery. Sources: FIRMS, Fire Information for Resource Management System, http://go.nasa.gov/27awNFg.

PT Tunas Sawa Erma 1B Concessions

Korindo subsidiary PT Tunas Sawa Erma 1B (PT TSE 1B), which holds an area of 19,000 hectares, began work in Papua in 2005. 25 local tribe clans own the majority of this land and have rejected Korindo’s plantation proposal. Nevertheless, in 2015, Korindo moved forward with land clearing in this area.

As the satellite images below show, there were 88 hotspots recorded in 2015 and six recorded in January 2016. By the end of April 2015, about 2,800 hectares had been cleared.

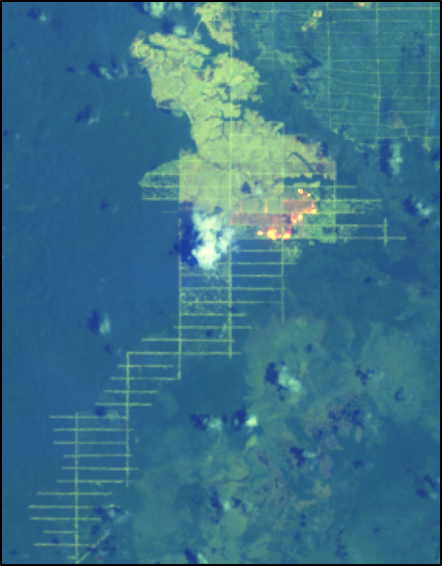

The massive fires set by Korindo on the PT TSE 1B concession are visible in the satellite image below, taken in late October 2015.

Satellite evidence gathered by Aidenvironment documents Korindo’s systematic use of fire. Landsat 8 imagery of Oct 24- Nov 1, 2015.

Satellite evidence gathered by Aidenvironment documents Korindo’s systematic use of fire. Landsat 8 imagery of Oct 24- Nov 1, 2015.

The brown color on the image below, taken in early May 2016, shows the area cleared by Korindo on the PT TSE 1B concession, which is about 500 hectares of primary forest and 2,300 hectares of secondary forest.

PT Berkat Cipta Abadi 1 (PT BCA 1) Concession

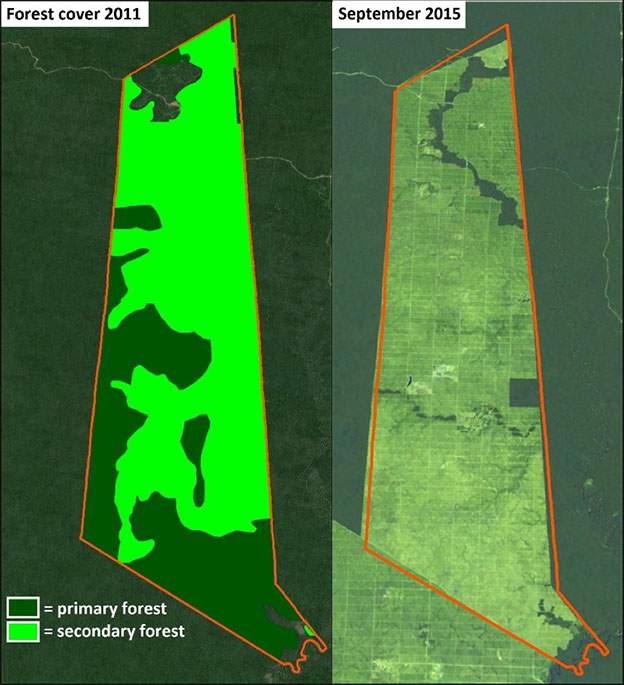

The entire PT BCA 1 concession area was forested before Korindo started its oil palm operations. During 2013 and 2014, a total of 4,500 hectares of primary forest were cleared, along with 8,700 hectares of secondary forest. Only a river corridor of 700 hectares was spared, as seen in the images below.

1: The entire concession area was forested before Korindo began its operations. Source: Indonesian Ministry of Forestry forest cover maps for 2011. 2: Korindo cleared 4,500 hectares of primary forest, along with 8,700 hectares of secondary forest. Only a river corridor of 700 hectares was spared. Source: Landsat 8 imagery for 22 to 30 September 2015.

1: The entire concession area was forested before Korindo began its operations. Source: Indonesian Ministry of Forestry forest cover maps for 2011. 2: Korindo cleared 4,500 hectares of primary forest, along with 8,700 hectares of secondary forest. Only a river corridor of 700 hectares was spared. Source: Landsat 8 imagery for 22 to 30 September 2015.

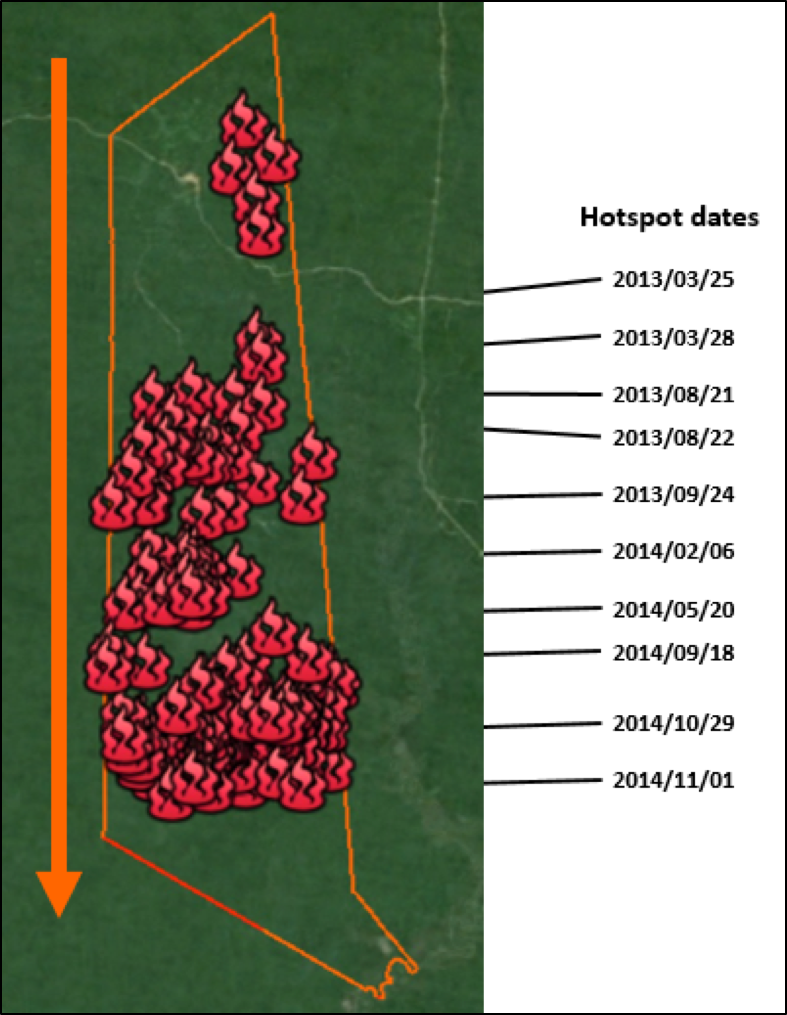

Land development began in the north and ended in the south. Hotspots followed deforestation and subsequent land development, as can be seen on the graphic below. In total, there were 106 hotspots recorded in 2013 and 2014. Burning is illegal under Indonesian law, and in addition, the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry specifically prohibited PT BCA from burning wood waste. Korindo ignored the extra warning and the fact that their fires are illegal, and continued burning.

The image below shows the spread of hotspots from north to south in 2013 and 2014 as Korindo cleared the land. Again, the pattern of fires closely mirrors Korindo’s land development, illustrating how the fires were not natural.

PT BCA hotspot pattern in 2013 and 2014.

PT BCA hotspot pattern in 2013 and 2014.

Illegality

In addition to being harmful for the environment and public health, burning to clear forests is illegal, prohibited under Indonesian Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management, among others. Possible penalties for those found guilty of breaking this law include fines and prison terms. In October 2015, the Papua Vice Governor Kleman Tinal spoke out against companies “that reduce the cost of clearing by burning” and said that companies that caused forest fires should be immediately shut down. The Singapore Transboundary Haze Law can also impose fines and jail time on foreign companies, like Korindo, driving haze in Singapore. The findings of this investigation will be filed with the Indonesian and Singaporean governments.

Korindo has gotten away with its forest burning- with one exception. In late 2015, Korindo received a permit suspension of three months due to fires in 2015 in one of its industrial timber concessions in Kalimantan.

Heavy equipment is used to pile the trunks of felled trees that will be unsustainably burned by Korindo's plantation company PT Papua Agro Lestari. Credit: Mighty.

Heavy equipment is used to pile the trunks of felled trees that will be unsustainably burned by Korindo's plantation company PT Papua Agro Lestari. Credit: Mighty.

Korindo vs Communities

Community Rights Abuses

In addition to environmental damage wrought by Korindo, the company has failed to recognize and respect the rights of many indigenous communities who have depended on the forests for centuries.

Korindo has not recognized the right of local communities to give or withhold their consent to any new developments on community lands (a concept known as Free Prior and Informed Consent or FPIC). Communities in North Maluku have lived there for hundreds of years and are, for the most part, strongly opposed to an oil palm plantation. The North Maluku branch of the Indonesian NGO Walhi is pursuing a lawsuit against Korindo. Villagers from five communities have called upon the Indonesian government to deny Korindo’s permit.

In April 2010, the Center for International Forestry Research interviewed workers, landowners, and people living adjacent to two of Korindo’s concessions. All three groups stated that the plantation had reduced their income from forest products and their ability to collect wood for housing and fuel. They also noted diminished access to food and income from forest resources. They had moved from self-sufficiency to dependence, fulfilling their daily food needs with subsidized rice. More than 60 percent of landowners and people in the vicinity of the plantations reported reduced water quality.

Local people in Papua do not receive any benefit from Korindo's oil palm plantation expansion on the land they have lived off of for centuries. Credit: Mighty

Local people in Papua do not receive any benefit from Korindo's oil palm plantation expansion on the land they have lived off of for centuries. Credit: Mighty

Although local indigenous groups are affected by Korindo’s work, they have minimal access to media to report illegal practices because Papua is extremely closed off to journalists and civil society. In addition, Korindo is well-connected with the armed forces in the area, and has been known to pressure or threaten local people who speak out against it.

Where Does Korindo's Palm Oil End Up?

Korindo's palm oil is used by consumers in Europe, North America, China, and India. Palm oil is used in soap, moisturizer, lipstick, cookies, shampoo, and many other products that we use every day. Fifty percent of consumer goods contain palm oil.

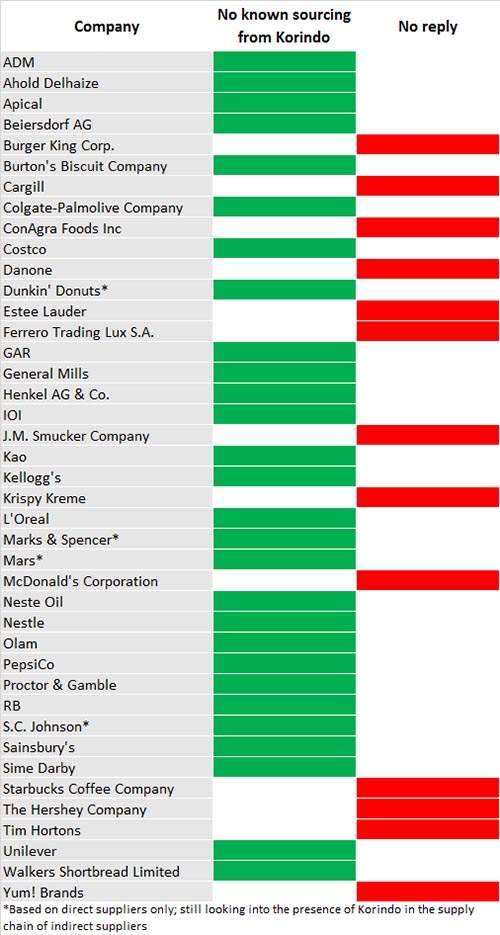

When asked by email whether or not they source from Korindo, directly or indirectly, here is how the major palm oil buyers responded. Please note that this was based on self-reporting and only reflects current sourcing from Korindo. Many of these companies likely had Korindo in their supply chain at one point.

Responses from major consumer companies that buy palm oil.

Responses from major consumer companies that buy palm oil.

Korindo's actions have already lost them several major customers, including palm oil traders Wilmar and Musim Mas who were direct buyers of Korindo, as well as indirect buyers who source from them - because it violated their "No Deforestation, No Peat, and No Exploitation" policies. Korindo's access to global markets is in serious jeopardy if it continues business as usual.

According to World Wildlife Fund, palm oil is used in about half of all packaged products sold in the supermarket.

According to World Wildlife Fund, palm oil is used in about half of all packaged products sold in the supermarket.

45% of the palm oil consumed in Europe is used for biofuel, according to a 2014 report by the European Federation for Transport and Environment.

45% of the palm oil consumed in Europe is used for biofuel, according to a 2014 report by the European Federation for Transport and Environment.

The Dirtiest Wind Energy

Korindo owns a company called KOUSA, which is based in Los Angeles, California. The firm sells wind towers to large companies like Siemens, Nordex, Suzlon, Iberdrola and Gamesa. Unfortunately, the benefits to the climate of the wind energy that these towers generate are eclipsed by the extreme toll that Korindo’s deforestation and burning takes on the environment. By sourcing from Korindo, these wind towers are helping finance deforestation, making this normally clean energy source dirty in this case. For these wind companies to be able sell truly clean energy, they should immediately cease purchases from Korindo, and turn to the many companies that manufacture wind turbines without deforestation.

Korindo's wind turbines. Credit: Korindo Wind Website

Korindo's wind turbines. Credit: Korindo Wind Website

What Does Korindo Need to Do to Clean Up its Act?

· Immediately enforce a moratorium on all new forest clearing and burning.

· Adopt and immediately implement a cross-commodity policy that protects high carbon stock landscapes (following the High Carbon Stock Approach available at http://www.highcarbonstock.org), high conservation value forests and peatlands of any depth, and that respects human, community, and labor rights. This policy should apply to all of Korindo’s global operations, subsidiaries, joint venture and supply chain partners. Korindo should also issue an implementation plan, work with a credible implementation partner, issue regular progress reports, and verify compliance through an independent third party.

· Cease all operations in PT Gelora Mandiri Membangun in South Halmahera (North Maluku), where Korindo is encroaching onto the customary lands of local communities, and immediately excise community customary lands from license areas.

· Address and remedy its legacy of environmental harm, land grabbing and human rights violations – including by returning customary lands, resolving social conflicts and grievances and restoring damaged ecosystems. Korindo needs to finance the restoration of an area at least equivalent to that which it has destroyed over the past two decades.

· Agree to broad transparency, including releasing the location of its mills and concession boundaries across all commodities, revealing the names and locations of third party suppliers, and reporting regularly on third party supplier compliance.

· Comply with any legal proceedings regarding Korindo’s use of fire to clear land and seizing control of customary lands without the consent of communities to whom those lands belong.

Take Action to Protect Tree Kangaroos

Tell Korindo enough is enough.

Sign this petition to demand Korindo agree to a moratorium on forest clearing and taking community lands and keep these forests from becoming a free-for-all for palm oil and timber companies.

Photo credit: Greenpeace/Tom Jefferson

Photo credit: Greenpeace/Tom Jefferson

Conclusion

This report documents Korindo’s destruction of 50,000 hectares of forest since 1998, and 30,000 since 2013. The tragedy of that recent deforestation is that it should have been stopped, the technology existed to stop it, and that it violated Indonesian law as well as the responsible sourcing commitments of its customers – but was allowed to continue so openly, for so long.

We hope that the Indonesian, Singaporean, and other governments will act immediately in response to the evidence presented here, and that buyers of Korindo’s palm oil, paper, wind turbines, and other products will cease to make any new purchases. But this campaign doesn’t end with action by Korindo. Korindo is just one company, but dozens of other cases show that, despite significant action by the private sector, even the leading palm oil, paper, and rubber companies are not doing enough to actually eliminate deforestation industry-wide and restore their reputation in the global marketplace. Automatic, transparent joint industry action modeled on the Brazilian soy moratorium should be the first step. (For more on this, see Glenn Hurowitz’s article in the Singapore Straits Times newspaper, “Straight talk about Indonesia’s Deforestation”).

The Indonesian and Malaysian governments also can monitor deforestation in near real-time, and send law enforcement authorities to stop and punish companies like Korindo. Why key government officials did not do so in this case is worthy of further investigation by anti-corruption bodies in each country. Finally, Singapore’s Transboundary Haze Law allows prosecutors to pursue criminal and civil liability against companies who contribute to Singapore’s haze. Korindo’s clear open burning and other illegal acts should make it a clear target for investigation by Singapore's law enforcement authorities.

Joint industry action coupled with robust government legal action is what is needed to make sure there are no more Korindos. Then, families of the future can know that tree kangaroos can continue hopping through their forest home forever.

Credit: Rhett A. Butler / Mongabay.com

Credit: Rhett A. Butler / Mongabay.com